Five notable gender gaps in 2025

If you are receiving this post via email it’s because at some point in the last year and a half you signed up for my Substack, Gender Gap. Sorry for the radio silence. I didn’t mean to take 2025 off from blogging here, but that’s what happened. But I'm back with a year-end wrap, highlighting five of the most interesting gender gaps that I've been filing away since last December. And I hope you'll stay subscribed because I plan to write more regularly in the new year!

1. “You know when it's time to go” – more women want to leave the U.S.

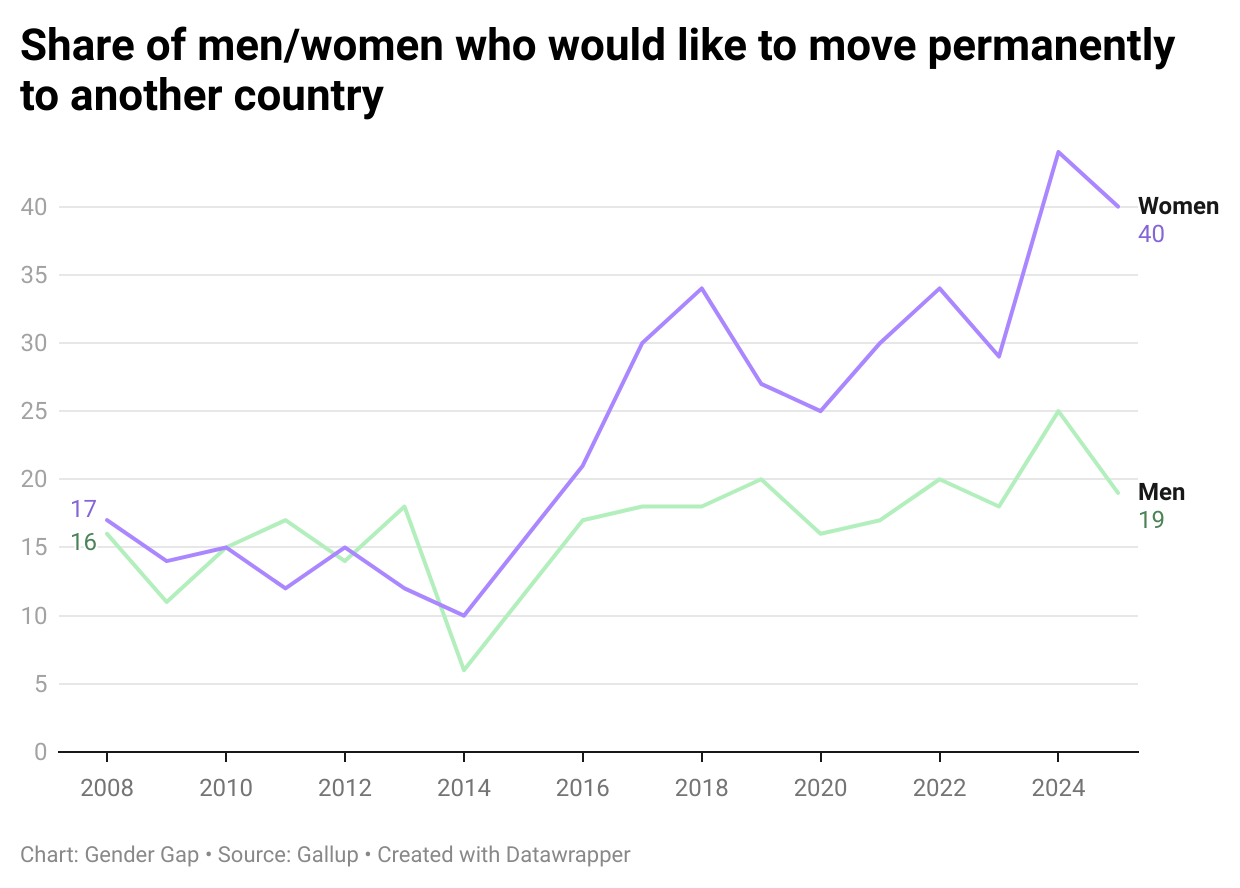

Many young women want to leave the U.S. Forever. A gender gap that made several headlines this year was the whopping 21 percentage-point difference in the share of men and women aged 15 to 40 in the U.S. who say they would like to move permanently to another country. Forty percent of women, but just 19 percent of men in this age cohort expressed this sentiment. It’s the widest gap recorded by Gallup, since they began asking this question in 2008.

The gender polarization on this question started in 2017, after President Trump took office to serve his first term. But it didn’t close considerably during the Biden years, and rose again with Trump’s second term. That maintained gap is a signal that men and women are drawing very different conclusions about whether the U.S. is a place where they can build the kind of future they want, regardless of who is in power. And while the Trump administration is a clear driver of this sentiment, even if Trumpism dies with Trump, I think this will be a difficult trend to reverse.

The Trump years has done something really interesting, which is likely driving this gender gap. Its made gender especially salient, even as it attempts to strip and ban related words from government documents and websites. In so doing, its made women especially gender conscious. And heighten gendered-consciousness fosters feelings of linked fate. For many women, this appears to have produced a form of political learning: a heightened sensitivity to how quickly political shifts can narrow future possibilities. In turn, they appear to possess a greater willingness to imagine bettering their future elsewhere, rather than adapting to the new normal.

2. High school boys are more likely to want to get married

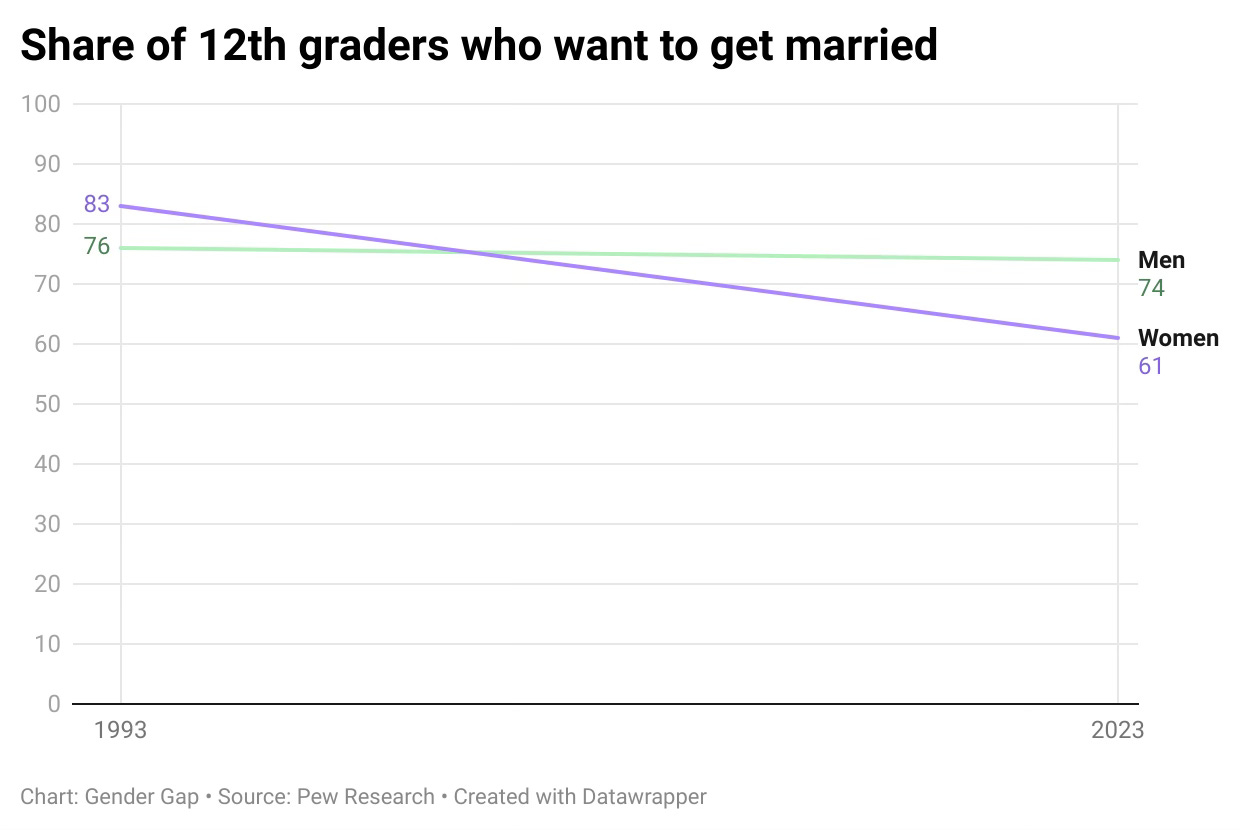

High school girls in 2023 are 22 percentage-points less likely to want to get married than high school girls in 1993 (Pew Research). It’s still a majority of young women who say they want to get married, but a notable drop, especially compared to their male counterparts, whose interest in marriage is largely steady.

Why are young women today less interested in marriage than their elders? Sure, there is the fact that women’s economic well-being isn’t as closely tied to marrying a man as it used to be. In this viral Instagram Reel by @davi87dp, he dryly makes this point to delighted women in the comments section (‘Men: “Choose better”; Women: “Ok, bet”’).

But the realization of this, and other relational dynamics, are where social media comes in, as a source for this gap. There is growing discourse online about the trials and tribulations of dating, and no shortage of social media accounts that teach young men to bait and control women. And young women online see this content, too.

The tradwife content is relevant here, as well. Yes, for many women they see this content as aspirational. But at a deeper level it is selling a gender essentialist view of married life that tells women they must be this or that, and in that way women who still recognize the capacity for a life of multitudes are going to be turned off from the institution all together.

I don’t think our divergent social media diets (see this WaPo story about TikTok feeds that only briefly touches on gender, but its there) explain every gender gap, but they are certainly somewhat related.

3. Social media is more “social” for women

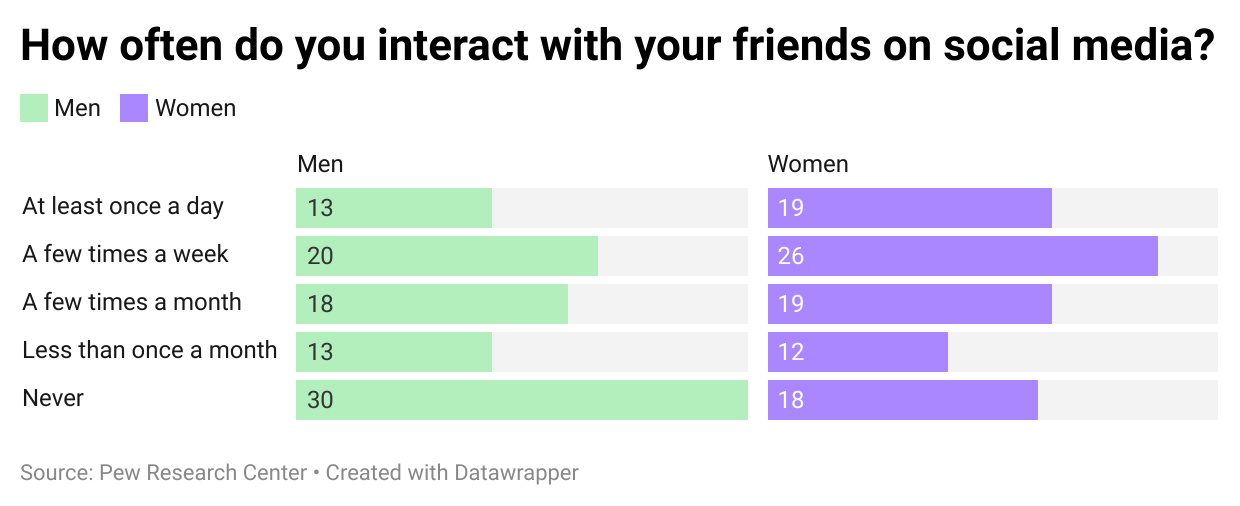

As I’ve written about, men are more active on “social” media sites where your network is loosely tied to shared interests rather than close personal relationships—e.g. Reddit, Twitter. As such, it’s not surprising, but still eye opening, to see that women are more likely to interact with their actual friends on social media than men.

According to a Pew survey, nearly one in three men (30%) say they “never” interact with their friends on social media, compared to 18% of women. Never??? Yet we know men are spending a lot of time online.

Sure, social media interactions are likely to be fragmented (e.g. non-continuous conversations) and I’d guess a lot of those exchanges are superficial (e.g. a long thread of shared posts, without much commentary beyond “LOL, it you”) and in this way, are a poor substitute for hanging out IRL. But the more time we spend online, these touch points with people from your everyday life become arguably more consequential.

In sum, the online lives of men and women are increasingly divorced, and this is just another piece of that puzzle. What looks like constant connectivity could mask a growing divergence in how men and women see the world, and relate to others.

4. Who’s lonely? It's not just men.

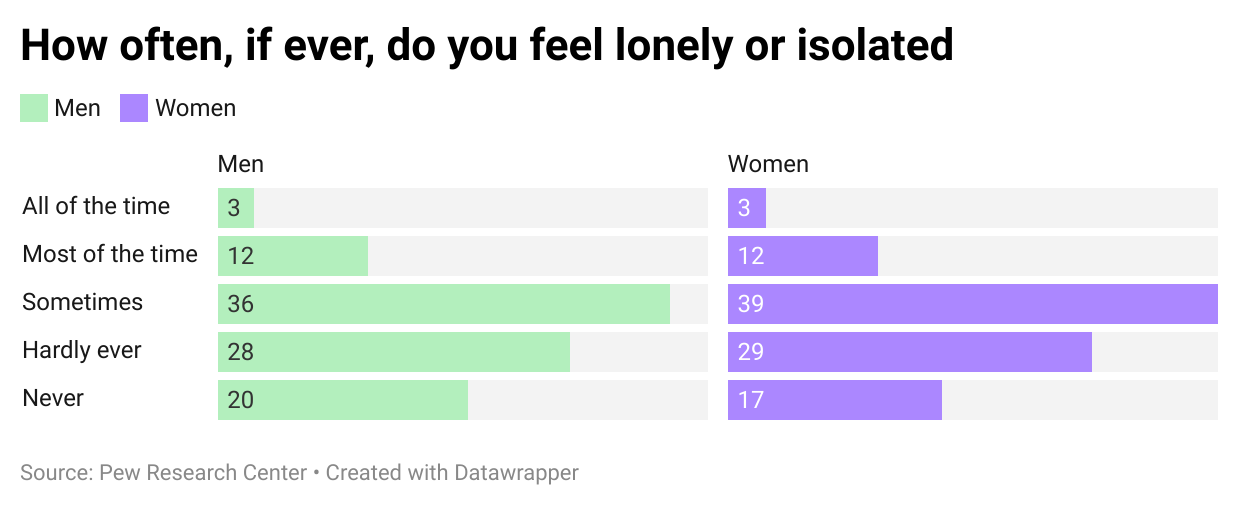

Attention to the “male loneliness epidemic” isn’t new—it’s been circulating in public conversation for years now. Even Saturday Night Live got in on it. What’s becoming clearer, though, is that loneliness isn’t actually a gendered anomaly. Men and women are both experiencing increasing isolation. Pew Research found that men and women responded similarly when asked “how often, if ever, do you feel lonely or isolated?” Aggregated data compiled by the American Institute for Boys and Men similarly shows little evidence of a gender gap on this measure.

So why the onslaught of scrutiny and attention to men’s loneliness plight but not women’s?

For one, lonely men are more likely to generate a care obligation for others. Angelica Puzio Ferrara, a postdoc at Stanford, has dubbed this “mankeeping,” which the New York Times defined as:

…the work women do to meet the social and emotional needs of the men in their lives, from supporting their partners through daily challenges and inner turmoil, to encouraging them to meet up with their friends.

Second, men’s loneliness is routinely filtered through dating and marriage discourse at precisely the moment when women are less likely to want to marry (see above). Straight men have historically relied on their partners for their social life, so if women exit these traditional partnerships, men’s loneliness is cast as a collective failure, often with women positioned as the fix.

Third, men’s suicide rate is higher than women’s, so there is greater urgency to understand and prevent any factor that could plausibly contribute to that outcome.

Setting aside why men’s loneliness is getting more attention than women’s, I am interested in whether the political implications of being lonely vary considerably for men and women. In other words, the question isn’t whether loneliness is gendered—it’s whether its political consequences are.

As a political scientist I am interested in whether these feelings of loneliness or isolation (or the shift in the burden of care) are actually correlated with different political behaviors, by gender. Does loneliness influence voting patterns, policy preferences, or civic engagement differently for men and women? Does loneliness prompt unique support responses that are politically consequential? E.g. We know that men are less likely to seek help of any kind for emotional support. Exploring these dynamics will help us understand if loneliness is a factor that shapes political life. This is something I am starting to explore with colleagues, so I might have more to say about this, empirically, in 2026.

5. More women than men want a college degree

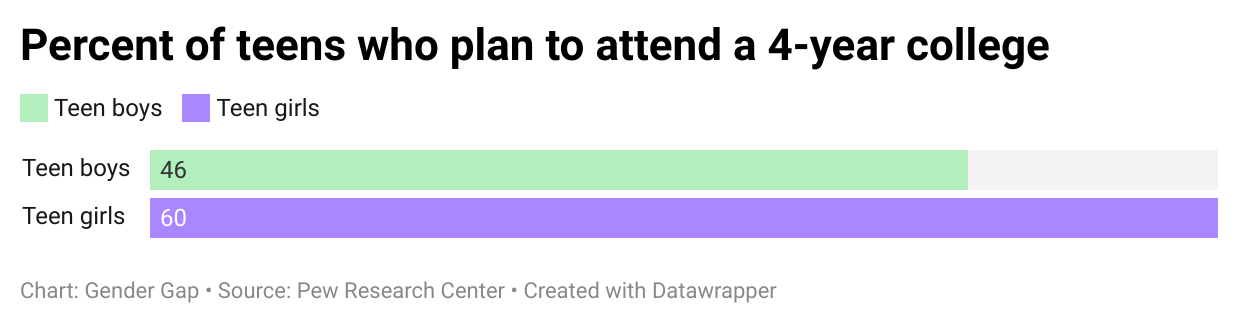

A more recent trend is that fewer men are going to college, and surveys suggest this is sticking, at least for the time being. A recent Pew survey found that 46% of teen boys—but 60% of teen girls—say they want to earn a college degree.

It’s not entirely clear why men are less drawn to college than they were a decade or so ago (men are more likely to say they don’t want or need a degree), but unlike the historic barriers women faced in accessing higher education, this isn’t obviously a social injustice. It’s a trend worth understanding—but not one that necessarily requires a restructuring of higher education to fix.

Writer and activist Soraya Chemaly wrote this sharp piece for The Atlantic that talks about the misguidedness of some of the reforms for this gap. She argues that school does not need to be redesigned to be more “boy-friendly;” the deeper issue is how boys are socialized to see competition and gender. In many educational settings, competitiveness is coded as something to be won only among other boys, which leads boys to interpret girls’ academic success as emasculating or illegitimate, which fosters withdrawal, resentment, or even aggression when boys are out performed by girls academically.

None of these gaps exist in isolation, and none feel especially fleeting. They’re signals about how men and women are imagining their futures, structuring their social lives, and navigating institutions that once promised stability or meaning. Some of these divides may widen; others may flatten or take on new forms. Either way, they’re worth watching as indicators of deeper shifts in social and political life in the U.S. I’ll be keeping an eye on these gaps (and more!) through 2026, with the goal of understanding not just whether they persist, but why they emerge and what it means for American democracy.

Excellent piece, Meredith! Ever since the 2024 election, it really does feel like gender has become the most important lens for understanding American politics, and I think these gaps you've identified explain so much about the (very odd) political moment we're living in.

Looking forward to your writing in 2026!

Great piece! I enjoyed reading your work at 538 and look forward to reading more in 2026.